Cross-posted from Channel Surfing:

Legal Services of New Jersey issued its annual poverty report, which found that more people in the state had trouble making ends meet in 2011 than at any time since the late 1950s.

The report‘s top findings were:

1. Record Poverty.

In 2011, poverty in New Jersey reached a record high not seen for the past 50 years. Census data going back to 1959 show that the official poverty rate of 10.4 percent in 2011 has not been surpassed in the last fifty years.

2. Nearly One-Third Face Significant Deprivation.

Using the Real Cost of Living, the portion of the state struggling to meet basic needs is dire — 31.5% were below 250% FPL in 2011. More than 2.7 million residents, or about 31.5 percent of the total population, were living in true or actual poverty in 2011; they were grappling to meet basic necessities.

3. Record Child Poverty.

Record number of children were living in poverty in 2011. About 780,000, or 38.5 percent of all children, were below 250% of FPL in 2011. Of these, 31.2 percent were below 200% of FPL and 14.7% were below 100% of FPL, all record highs for the state.

4. Extreme Poverty In Certain Municipalities.

Municipal poverty was highest in Camden, where 64.5 percent of the total population lived in households with incomes below 200 percent of FPL, followed by Passaic with a poverty rate of 59.5 percent, Lakewood at 55.9 percent, Paterson at 53.3 percent, Trenton at 51.5 percent, and Newark at 50.4 percent.

5. Child Poverty In Extreme Poverty Municipalities.

Child poverty rates were highest in Camden — 79 percent of all children were below 200 percent of the FPL in 2011. In another six places – Passaic, Lakewood, Paterson, Trenton, Newark, and Union City — more than 60 percent of children were below 200 percent of the FPL.

6. Continued High Unemployment.

In July 2013, the unemployment rate in New Jersey was 8.6 percent, substantially higher than the 4.6 percent at the onset of the Great Recession, and even higher than the current national average of 7.4 percent. The most recent data for July 2013 shows that New Jersey had the seventh highest unemployment rate in the nation.

7. Record Food Insecurity.

Food insecurity reached another all-time high in 2011. A sizeable portion of New Jersey households did not have enough food for all their members in 2011. Data from a three-year period (2009-11) show that 12.3 percent of New Jersey households were food insecure at some point during that period, and 4.5 percent had very low food security, meaning that the food intake of one or more household member was reduced or their eating pattern disrupted due to lack of resources. This represents a record high for the fifth consecutive year.

8. High Level of Medically Uninsured.

Working-age population below 200% FPL had very high rates of uninsurance in 2011. Working adults with low incomes were much more likely than either children or the elderly to be without health insurance coverage. In 2011, a sizeable proportion of working adults with incomes below 200 percent of the FPL were without health insurance — 41.7 percent of working adults below 50% FPL, 38.2 percent between 50-99% FPL, and 42.4 percent with incomes between 100-200% FPL.

9.Poverty Correlates with School Districts Needing Improvement.

School districts failing to make adequate progress were more likely to be located in high poverty areas. During 2011-12, 19 category “A” school districts (poorest in the state) were identified as needing improvement. The “J” districts (considered the most affluent in the state) did not have any schools identified as needing improvement. In addition, the number of “A” district schools needing improvement has increased significantly in the past three years. During the 2009-10 school year, 13 failing districts fell under the “A” classification. By 2011-12 school year, the number rose to 19, a 46 percent increase. In all three years, no “J” district schools were identified as needing improvement.

Officials with Legal Services said about a quarter of the state’s residents were considered poor in 2011″nearly 1 percent

higher than the previous year and 3.8 percent more than pre-recession

levels,” according to NJ.com.

“This is not just a one-year or five-year or 10-year variation,” said Melville D. Miller Jr., the president of LSNJ, which gives free legal help to low-income residents in civil cases. “This is the worst that it’s been since the 1960 Census.”

The numbers could get worse, LSNJ said (according to NJ.com):

The report warned Census figures for 2012 to be released this month may be higher. Those numbers are expected to show some of the impact from Hurricane Sandy, which took a bite out of the state’s economy and destroyed a large amount of affordable housing.

New Jersey is not alone, Miller said.

In 2011, the federal poverty rate was the largest it had been in 18 years, according to the Congressional Research Service.

“The Great Recession was the worst major economic event since the early ’30s,” Miller said. “It’s taken longer for the U.S. to come out of it.”

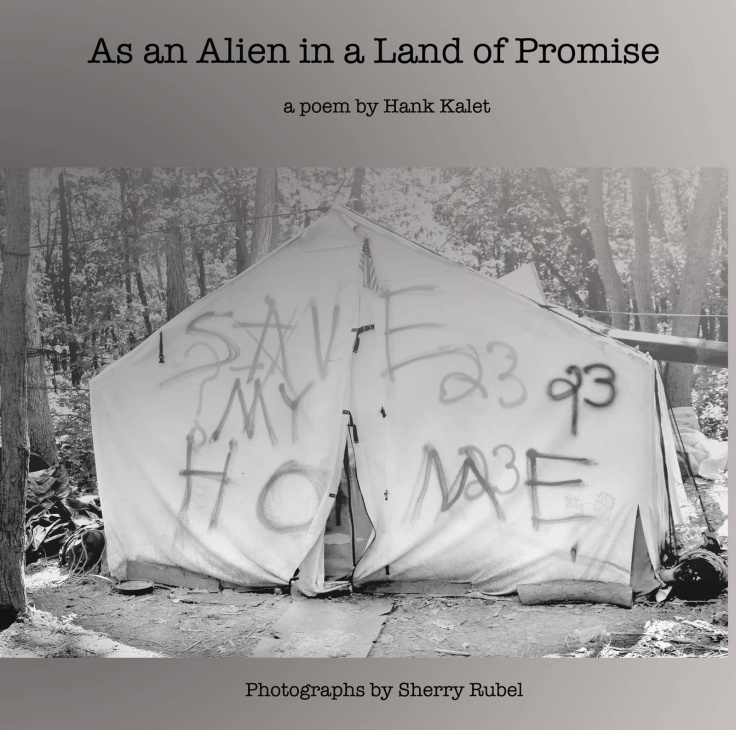

I wrote this essay a couple of years ago, though I feel it remains valid. We must see the homeless, the poor, the refugee as human. We have to grant them their personal agency. We cannot, as we have for too long, imposed a hypocritical moral posture on them.

I wrote this essay a couple of years ago, though I feel it remains valid. We must see the homeless, the poor, the refugee as human. We have to grant them their personal agency. We cannot, as we have for too long, imposed a hypocritical moral posture on them.